(Summary of initial investigation)

William Storage and Laura Maish

Email us

about this page

|

Craniofacial Anthropometry of some

Julio-Claudian Portraits (Summary of initial investigation) William Storage and Laura Maish

|

Home |

| Addendum - May 5, 2009 - Since posting this piece in late

2007, we have refined our selection of craniofacial landmarks used for

comparing Julio-Claudian portraits, finding that we actually can

differentiate many of the portrait types based solely on craniofacial

proportion measurements. After our original investigation, we made 3-D

scans of some key portraits. The ability to superimpose the resulting

computer models allowed us to identify a number of cranial proportions

not used in our first look, but very useful in differentiating the

portraits. Many of these proportions are more basic and fundamental to

an anthropometric description of a head than those listed below. In

hindsight, we realized that several such measurements, while useful for

characterizing a skull, are of little use in plastic surgery and were

therefore not present in the list used by Farkas, et. al. As an example

of a key proportion in our new list, consider face width to

tragion-nasion distance. This proportion is not useful in aesthetic

plastic surgery because ears cannot be moved. It isn't really useful in

reconstructive surgery because other features would control the location

of the nasal bridge and surrounding structure. The proportion is always

much greater on Caligula portraits than on Augustus portraits not

recarved from portraits of Caligula. Consequently, it provides a strong

clue as to whether a portrait with Augustus's characteristic hair locks

- obviously intending to portray Augustus - was derived from an earlier

portrait of Caligula. We'll update this page in the near future. |

Hairstyle has long been the principle means of identifying the subjects of

Julio-Claudian and later imperial portraits. Recently, a few scholars have

proposed that we may be overly reliant on this approach, the

Lockenzahlmethode,

as named by the Romische

Herrscherbild series of books. In order to investigate the

possibility that physiognomic characteristics might be undervalued in the

process of identifying uncertain portraits, we conducted a preliminary study,

collecting measurements of marble portraits, normalized by calculating ratios of

various measurements. This technique is in common usage in the analysis of human

craniofacial anthropometry for reconstructive and aesthetic plastic surgery.

We used fifty eight of the proportion indices identified by Farkas and Munro (1986), selected for the ability of their facial landmarks to be located in photographs of frontal and profile views of the sculptures. A few of these still required approximations because of the presence of hair or at landmarks that in a human would be better located by palpation. We included sculptures with restored noses in cases where enough of the original nose was present to reasonably estimate vertical position of the pronasale and where enough original marble existed to establish nasofrontal and nasolabial angles. Most proportions involving ears were excluded, since few sculptures retain original ears. Proportions involving facial contours were also excluded, since they cannot be accurately derived from photographs. Laser-scanning of the portraits would provide more and better data, using techniques common in both plastic surgery and character animation for movie special effects (Aung 1995, Enciso 2003).

We wrote a computer program that displays frontal and profile photographs on screen and allows us to identify the facial landmarks (figure 1). The program records the coordinates of the facial landmarks (listed in Table 2) in a database, from which facial proportions and statistical calculations are made and reported. This approach, including use of photos, as opposed to measurements of the head itself, is accepted in facial plastic surgery applications, provided that the photos meet certain criteria (e.g. clarity, facial plane alignment, large subject-camera distance compared to head height). We adhered to the criteria identified in guidelines for use of photos in plastic surgery.

Our analysis of 25 portraits of Augustus, Caligula, Claudius and Germanicus indicates that craniofacial anthropometry is of limited use in portrait identification. A comparison of facial proportions of Augustus and Caligula illustrate the problem. Few statistically significant differences in average measurements of craniofacial proportions and facial angles can be seen (Table 3). Generally, the standard deviation for a given proportion of one subject is comparatively large when compared to the difference between the mean value of that proportion for the other subjects. Excluding the proposed Caligula/Augustus recarvings does not help the problem at all. Surprisingly, an analysis of the difference between Augustus heads and proposed Caligula/Augustus heads shows that for most of the proportions where a difference exists, it is in the wrong direction. For example, the average mandibulo-upper face height index is lower for Caligula/Augustus heads than for Augustus heads, yet the index is higher for Caligula heads than for original Augustus heads. Similarly, the mean mandibulo-lower face height index of Caligula/Augustus heads is lower than that of original Augustus heads, yet the index is higher for Caligula than for Augustus. Of the 58 proportions analyzed, the 21 listed below were found to be most significant. These proportions are listed below (Table 1).

| proportion index | proportion name | numerator | denominator |

| 2 | lower face-face height index | subnasale – gnathion | nasion – gnathion |

| 3 | mandibulo-face height index | stomion – gnathion | nasion – gnathion |

| 4 | mandibulo-upper face height index | stomion – gnathion | nasion – stomion |

| 5 | mandibulo-lower face height index | stomion – gnathion | subnasale – gnathion |

| 8 | nasal index | alare (r) – alare(l) | nasion – subnasale |

| 9 | upper lip height-mouth width index | subnasale – stomion | chelion (r) – chelion (l) |

| 10 | cutaneous-total upper lip height index | subnasale – labiale superius | subnasale – stomion |

| 11 | vermilion-total upper lip height index | labiale superius – stomion | subnasale – stomion |

| 12 | vermilion-cutaneous upper lip height index | labiale superius – stomion | subnasale – labiale superius |

| 14 | vermilion height index | labiale superius – stomion | stomion – labiale inferius |

| 15 | chin-mandible height index | sublabiale – gnathion | stomion – gnathion |

| 19 | nose-mouth width index | alare (r) – alare (l) | chelion (r) – chelion (l) |

| 23 | lower lip-face height index | stomion – sublabiale | subnasale – gnathion |

| 25 | lower lip-chin height index | stomion – sublabiale | sublabiale – gnathion |

| 28 | mandible Width - face height index | stomion – gnathion | nasion – gnathion |

| 29 | mandibular index | stomion – gnathion | gonion (r) – gonion (l) |

| 30 | Face height index | nasion – gnathion | trichion – gnathion |

| 32 | mandible width - total face height index | gonion (r) – gonion (l) | trichion – gnathion |

| 35 | eye fissure index | palpebrale superius – palpebrale inferius | exocanthion - endocanthion |

| 52 | intercanthal - skull base width index | endocanthion (r) – endocanthion (l) | tragion (r) – tragion (l) |

| 54 | intercanthal - nasal width index | endocanthion (r) – endocanthion (l) | alare (r) – alare (l) |

Table 1: Most significant facial proportions as determined by statistical analysis of 25 Julio-Claudian portraits examined.

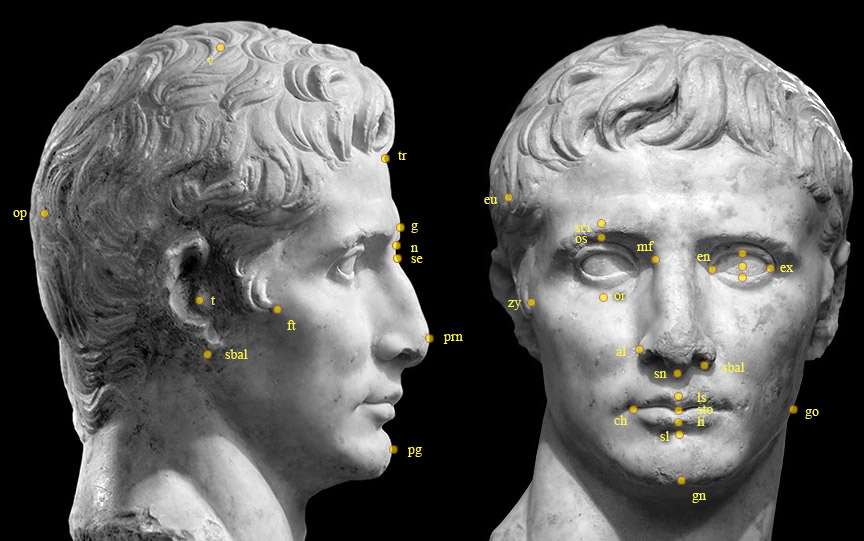

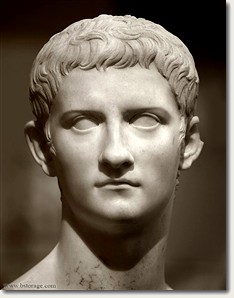

Figure 1. The Getty Caligula/Augustus showing facial

landmarks identified in frontal and profile photos

| v | vertex | highest point of head |

| g | glabella | most prominent point between the eyebrows |

| op | opisthocranion | situated in the occipital region of the head is most distant from the glabella |

| eu | eurion | most prominent lateral point on each side of the skull in the area of the parietal and temporal bones |

| tr | trichion | point on the hairline in the midline of the forehead |

| zy | zygion | most lateral point of each of the zygomatic |

| go | gonion | most lateral point on the mandibural |

| sl | sublabiale | Determines the lower border of the lower lip or the upper border of the chin |

| pg | pogonion | most anterior midpoint of the chin, located on the skin surface in the front of the identical bony landmark of the mandible |

| gn | menton (or gnathion) | lowest median landmark on the lower border of the mandible |

| en | endocanthion | point at the inner commissure of the eye fissure |

| ex | exocanthion (or ectocanthion) | point at the outer commissure of the eye fissure |

| p | center point of pupil | Is determined when the head is in the rest position and the eye is looking straight forward |

| or | orbitale | lowest point on the lower margin of each orbit |

| ps | palpebrale superius | highest point in the midportion of the free margin of each upper eyelid |

| n | nasion | intersection of the frontal and two nasal bones |

| pi | palpebrale inferius | lowest point in the midportion of the free margin of each lower eyelid |

| os | orbitale superius | highest point on the lower border of the eyebrow |

| sci | superciliare | highest point on the upper border in the midportion of each eyebrow |

| se | sellion (or subnasion) | Is the deepest landmark located on the bottom of the nasofrontal angle |

| al | alare | most lateral point on each alar contour |

| prn | pronasale | most protruded point of the apex nasi |

| sn | subnasale | midpoint of the angle at the columella base where the lower border of the nasal septum and the surface of the upper lip meet |

| sbal | subalare | point at the lower limit of each alar base, where the alar base disappears into the skin of the upper lip |

| ac | alar curvature (alar crest) point | most lateral point in the curved base line of each ala |

| ls | labiale (or labrale) superius | midpoint of the upper vermillion line |

| li | labiale (or labrale) inferius | midpoint of the lower vermillion line |

| ch | cheilion | point located at each labial commissure |

| sto | stomion | Intersection of vertical facial midline and horizontal labial fissure between closed lips |

| sa | superaurale | highest point of the free margin of the auricle |

| sba | subaurale | lowest point of the free margin of the ear lobe |

| pa | postaurale | most posterior point on the free margin of the ear |

| obi | otobasion infrious | point of attachment of the ear lobe to the cheek |

| po | porion (soft) | highest point of the upper margin of the cutaneous auditory meatus |

| t | tragion | notch on the upper margin of the tragus |

Table 2: Description of facial landmarks.

| Prop. No./ | Augustus | Caligula | Claudius | Germanicus | ||||

| Sample count | 7 | σ | 4 | σ | 8 | σ | 6 | σ |

| 2 | 0.46 | 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.01 |

| 3 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.01 |

| 4 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.03 |

| 5 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.7 | 0.03 | 0.71 | 0.03 |

| 8 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.03 |

| 9 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.07 |

| 10 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.10 | 0.69 | 0.04 |

| 11 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.04 |

| 12 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.48 | 0.06 | 0.74 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.09 |

| 14 | 0.78 | 0.17 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.17 | 0.93 | 0.07 |

| 15 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.71 | 0.04 |

| 19 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.88 | 0.01 |

| 23 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| 25 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.08 | 0.41 | 0.08 |

| 28 | 1.01 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.03 |

| 29 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.02 |

| 30 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.02 | 0.79 | 0.03 |

| 32 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.05 |

| 35 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.04 |

| 52 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.02 |

| 54 | 1.02 | 0.07 | 0.91 | 0.14 | 0.98 | 0.09 | 0.96 | 0.09 |

Table 3: Craniofacial proportion values and standard deviations for selected indices.

Some, but not all, of the most significant differences between facial

proportions of the portraits are readily seen by most viewers. Compared to the

others, Claudius has a relatively large distance from upper lip to bottom of

nose and a more triangular-shaped face. These features are often mentioned in art-history

pieces on

identifications of imperial portraits. Our measurements occasionally - although

barely, and not truly statistically significantly - show counterintuitive

results. For example, Augustus's mandibulo-lower face height index and related

ratios are almost always smaller than those of Caligula, who is typically

described using terms like "weak chin". Values of this index

for all four subjects fall within one standard deviation of the mean value of

this index for humans (all races) as reported by Farkas (1986). In all other

measurements except for eye size, we found the portraits to be lifelike.

Art history literature often mentions the supposed application of the canon of Polycleitos to portraits of Augustus. If such a canon in fact existed, it seems unlikely that it included facial proportions, assuming that sculptors of imperial portraits were proficient enough to apply a canon, had it existed. Based on craniofacial measurements that can be made from frontal and profile photos, Augustus is almost indistinguishable from Germanicus. Some skeptical art historians (e.g., Andrew Stewart, 1978) appear to doubt that the canon of Polycleitos amounted to much more than theory. Facial canons formed by artists of the Renaissance were found by Farkas (1986, 2005) and Edler (2006) to be inconsistent with average proportions of humans - and inconsistent with proportions found in faces judged beautiful by surgeons, international beauty contest judges, and popular vote. In summary, it appears that facial canons are little more than numerology.

Summary

Our findings are, in many ways, "negative results". Craniofacial proportions do

not so far appear to be useful in differentiating Julio-Claudian portraits.

Further analysis might find them to be more useful in determining whether two

portraits of less naturalistically rendered portraits were carved by the same

hand, or whether two portraits with facial characteristics farther from the mean

are likely to be of the same subject. It may also be that the ears and the nose

in particular are far too important to not be considered, as they are generally

not considered here.

Future Study

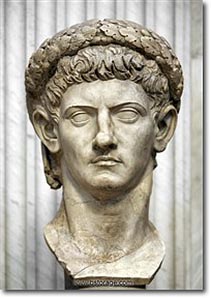

We discovered, unexpectedly, that many of the portraits showed certain facial

asymmetries not found in normal human faces. Most predominant was a large

difference between the vertical distances from left exocanthion to left cheilion

compared to the same measurement on the right side of the face. This is somewhat

visible in the photo of Claudius below (2nd from left). A nominally horizontal

line extended from the corners of his mouth would intersect a line drawn through

his pupils at a surprisingly steep angle. We later found that at least one art

historian has reported on this condition in portraits, and speculated on the

reason for it. We think this warrants another look. The existing tools we

developed to analyze facial proportions will be useful in collecting and

reducing data on facial asymmetries. Measurements of facial contours (requiring

3-dimensional scanning) may also show be more informative than the data that can

be extracted from photos.

- Bill Storage - 11/11/2007

S. Aung, R. Ngim, and S. Lee, "Evaluation of the laser scanner as a surface

measuring tool and its accuracy compared with

direct facial anthropometric measurements," British Journal of Plastic

Surgery, 48, 551-558, 1995.

(e.g.,) Dietrich Boshung, Die Bildnisse des Augustus, Das romishe Herrscherbild, pt. 1, vol. 2 Berlin: Gebruder Mann Verlag, 1993. DM 290

Raymond Edler , Pragati Agarwal , David

Wertheim , and Darrel Greenhill. "The use of anthropometric proportion indices

in the measurement of facial attractiveness"

The European Journal of Orthodontics Advance Access published on January

13, 2006, DOI 10.1093/ejo/cji098.

Farkas, L. G., Katic, M. J., et. al., "International anthropometric study of facial morphology in various ethnic groups/races", Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 16, 615 (2005).

Leslie G.,. Farkas and Ian R. Munro. Anthropometric Facial Proportions in Medicine, 1986. ISBN-13: 978-0398052614.

Reyes Enciso, Alex Shawa, Ulrich Neumannb, and JamesMaha, 3D head anthropometric analysis, 2003 Online PDF document

Andrew Stewart; A. F. S. "The Canon of Polykleitos: A Question of Evidence," The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 98. (1978), pp. 122-131.

Copyright 2007 William Storage. All rights reserved.